Want to learn more about the painting you found while clearing out the attic? What about the drawing that has been hanging in grandma’s hallway since you were a kid? Maybe the sculpture you found at the flea market last summer really is a Remington. How can you find out?

For answers, be prepared for a little detective work. We hope these tips and resources will help you begin, but remember that these lists are not exhaustive. Whether you research a family heirloom or a yard-sale find, the process can be rewarding!

OKAY, LET’S INVESTIGATE!

- First Steps

- Know the artist’s name? Go to Biographical Resources.

- See a mark or signature you cannot identify? Check out Signatures, Monograms, and Markings.

- To learn about the history of a particular artwork, go to Exhibition Guides and Provenance.

- If all else fails, try Encyclopedias and Surveys.

- How Much Is Your Object Worth?

- Want to Research Prints or Find Posters?

- Find out How to Care for Your Collections.

- Want more? Resources for in-depth art research.

First Steps – Researching Your Art

Like any good detective, begin with what you know. Gather the following information:

- What is the title or subject of the work?

- Where and when was it made? If you do not know the exact year, perhaps you can guess an approximate date.

- How long has the work belonged to you or your family? Check family records and interview relatives who might know something about the artwork. If you recently acquired your treasure, try to obtain as many details as possible from the seller, dealer, or previous owner.

- If you are researching a painting, can you determine its style? Is it realistic or impressionistic? Is it abstract or representational?

After reviewing the information you have, determine what else you want to learn. Such questions will guide your research.

Many printed and online resources can help you investigate your artwork. The best place to start is your public library. There a librarian should be able to direct you to helpful books, clipping files, and online databases or indexes.

If you live near a university or art museum, check to see if their libraries are open to the public. They will likely have many of the specialized art resources listed in this guide. Do not overlook state or local historical societies, as they may also have a wealth of information. Archives and art museum libraries are usually open by appointment only, and you will need to contact them in advance for access to their materials.

Biographical Resources

If you know the artist’s name, consult biographical dictionaries to learn some basic, but important facts about the artist. Often, these publications are organized by regions (e.g., Dictionary of New Orleans Artists), by subject (e.g., Dictionary of Marine Artists), by media (e.g., Dictionary of Western Sculptors in Bronze), or by time periods (e.g., Handbook of 17th-, 18th- and 19th-Century American Painters). Please see our Appendix: Want to Learn More? for a comprehensive bibliography.

Biographical dictionaries provide vital statistics, including life dates; locations of birth, death, and activity; school affiliations including where the artist studied or taught; and memberships in artistic clubs or societies such as the National Academy of Design. Some dictionaries also provide variant spellings of the artist’s name, information on when and where the artist exhibited, or list the whereabouts of the artist’s major works. Because an artist might be listed in more than one dictionary, checking several might help you develop a greater understanding of the artist.

DICTIONARIES OF AMERICAN ARTISTS

- Falk, Peter Hastings, ed. Who Was Who in American Art. Madison, Conn.: Sound View Press, 1999.

- Groce, George C., and David H. Wallace, eds. The New-York Historical Society’s Dictionary of Artists in America, 1564–1860. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957.

- Havlice, Patrice Pate, ed. Index to Artistic Biography. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1981–.

- Igoe, Lynn Moody, and James Igoe. 250 Years of Afro-American Art: An Annotated Bibliography. New York: R.R. Bowker, 1991.

- Optiz, Glenn B., ed. Dictionary of American Sculptors: 18th Century to the Present. Poughkeepsie, N.Y.: Apollo Book, 1984.

- Optiz, Glenn B., ed. Mantle Fielding’s Dictionary of American Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers. Poughkeepsie, N.Y.: Apollo Book, 1983.

DICTIONARIES OF INTERNATIONAL ARTISTS

If the artist you’re researching is not listed in the sources above, check more comprehensive international dictionaries. Plus, see our bibliography section in the Appendix: Want to Learn More? which lists some specialized dictionaries that group artists by region or media.

- Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon. Munich: K.G. Saur, 1992–.

- Benezit, E., ed. Dictionary of Artists. Paris: Gründ, 2006.

- Mallet’s Index of Artists, International-Biographical, Including Painters, Sculptors, Illustrators, Engravers and Etchers of the Past and Present. New York: Peter Smith, 1948.

- Petteys, Chris, ed. Dictionary of Women Artists: An International Dictionary of Women Artists Born Before 1900. Boston: G.K. Hall, 1985.

- Thieme-Becker, ed. Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler. Leipzig: Verlag Von Wilhelm Engelmann, 1907–1913.

SOURCES FOR CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS

Contemporary artists are often more difficult to research. Do not give up too quickly though. Many contemporary artists have personal Web sites. Try entering the artist’s name in an Internet search engine such as Google or Yahoo. If the artist does not have a Web site you still may discover a press release from an exhibition or a newspaper or magazine article. When you’ve exhausted online resources, consider the following printed materials:

- Dictionary of Contemporary American Artists. Ed. Paul Cummings. New York: St. Martins Press, 1994.

- New York Public Library: The Artists File (microfiche). Alexandria, Va.: Chadwyck-Healy, Inc., 1987–1989.

- Who’s Who in American Art. New Providence, N.J.: R. R. Bowker, annual.

ONLINE ARTIST BIOGRAPHIES

There are surprisingly few comprehensive online sources for artist biographical information. Try these art specific sources:

The Getty Research Institute maintains the Union List of Artist Names at http://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/ulan/index.html. While this online database does not always include biographies, the index does supply the artist’s name, variant spellings, life dates, nationality, and related bibliographic citations.

Some larger biography sites reference major artists.

Signatures, Monograms, and Markings – Researching Your Art

Naranjo, “Storyteller #1,” November 14, 1987

If you have only a signature or initials and cannot identify the artist, consult an artist signature or monogram dictionary.

- Castagno, John, ed. American Artists: Signatures and Monograms, 1800–1989 (Vols.1-3). Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1990–2009.

- Castagno, John, ed. Artists as Illustrators: An International Directory with Signatures and Monograms 1800 to the Present. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1990.

- Castagno, John, ed. European Artists: Signatures and Monograms, 1800-1990. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1990.

- Falk, Peter Hastings, ed. Dictionary of Signatures and Monograms of American Artists. Madison, Conn.: Sound View Press, 1988.

- Jackson, Radway, ed. The Visual Index of Artists’ Signatures and Monograms. London: Cromwell Editions, 1991.

FOUNDRY AND MATERIAL SUPPLIER DICTIONARIES

Be aware that not all names found on an object belong to the artist. For example, previous owners may have written their names on the back of an object. Often, for cast or fabricated sculptures, the foundry or fabricator’s name or monogram appears on the base of the sculpture or in another inconspicuous place. Sometimes the material supplier’s name can appear on a work or an attached label. Foundry and material supplier dictionaries can help you identify these marks and establish where your artist might have been active.

- Berman, Harold. Bronzes: Sculptors & Founders: 1800–1930. Chicago: Abage Publications, 1974–ca. 1981.

- Edge, Michael S. Directory of Art Bronze Foundries. Springfield, Ore.: Artesia Press, 1990.

- Forrest, Michael. Art Bronzes. West Chester, Pa.: Schiffer, 1988.

- Katlan, Alexander W. American Artists’ Materials Suppliers Directory Nineteenth Century: New York 1810–1899; Boston 1823–1877. Park Ridge, N.J.: Noyes Press, 1987.

- Katlan, Alexander W. American Artist’s Materials: A Guide to Stretchers, Panels, Millboards, and Stencil Marks. Madison, Conn.: Soundview Press, 1992.

- Shapiro, Michael Edward. Bronze Casting & American Sculpture: 1852–1900. Newark, Del.: Univ. of Delaware Press, 1985.

Exhibition Guides and Provenance – Researching Your Art

Facts about an artwork’s history can prove elusive. Titles of works may change over the years. Plus, dimensions often vary slightly, depending on how measurements were taken. For tracking provenance (the location of an artwork prior to its current ownership), start with exhibition guides in print. Consult auction indexes, collection catalogs or inventories, catalogues raisonné, and archival files and records.

For nineteenth-century and earlier works, search the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s online Pre-1877 Art Exhibition Catalogue Index—a list of 950 exhibitions held in this country through 1876. You can also consult the following exhibition guides:

- The Annual Exhibition Record of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Madison, Conn.: Soundview Press, 1988–1989.

- Cowdrey, Mary Bartlett, ed. American Academy of Fine Arts & American Art-Union, 1816–1852. New York: New-York Historical Society, 1953.

- Marlor, Clark S., comp. A History of the Brooklyn Art Association with an Index of Exhibitions. New York: James F. Carr, 1970.

- Naylor, Maria, comp. National Academy of Design Exhibition Record: 1826–1860, 1861–1900. New York: Kennedy Galleries, 1973.

- Perkins Jr., Robert F., and William J. Gavin, III, comps. Boston Athenaeum Art Exhibition Index 1827–1874. Boston: Library of Boston Athenaeum, 1980.

- Rutledge, Anna Wells, ed. Cumulative Record of Exhibition Catalogues: The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1955.

Encyclopedias and Surveys – Researching Your Art

For more in-depth information, ask your local librarian to help you search the library’s online catalog. There you might find books or exhibition catalogs featuring your artist.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum’s library catalog (like many other museum or university catalogs) can be searched via the Internet at www.siris.si.edu. If you find a book that interests you, check with your local library to see if they have it or can borrow it through interlibrary loan.

To find relevant articles in magazines or journals, look for the artist’s name in periodical indexes such as Art Index or Art Bibliographies Modern. Makers of decorative arts, designers, or craftspeople might be indexed in Design and Applied Arts Index.

After locating a relevant book or article, check out the accompanying bibliographies for sources you might not have already discovered.

To find out which museums own works by a particular artist, search the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s national Inventories of American Painting and Sculpture available on the web through SIRIS (the Smithsonian Institution Research Information System) at www.siris.si.edu.

Do not be discouraged if you cannot find an artist listed in standard biographical resources. Even though the artist might not have a national following, he or she might be well known regionally. If the artist is native to your area or if you know of an associated geographical location, try contacting state or local historical societies for unpublished information in their files. Some larger public libraries and museum art libraries maintain ephemera files on artists active in their areas.

With or without the artist’s name, there is still plenty to discover about your object. If you have clues regarding the title, style, or date of the work, but no artist information, you can still track the origins of your object with careful research. Look for well-illustrated exhibition catalogs or general art survey books to see if you can find any similar works that would help match your artwork to a particular “school of artists.”

ENCYCLOPEDIAS

- Encyclopedia of World Art

- Grove’s Dictionary of Art

- McGraw Hill Dictionary of Art

- Oxford Dictionary of American Art and Artists

- Praeger Encyclopedia of Art

- Yale Dictionary of Art and Artists

GENERAL SURVEY BOOKS

- Bjelajc, David. American art: a cultural history. New York: H.N. Abrams, 2001.

- Brown, Milton W. American Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Decorative Art, Photography. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986.

- Craven, Wayne. Sculpture in America. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1984.

- Doss, Erika. Twentieth-Century American Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Fineberg, Jonathan. Art Since 1940. Upper Saddle River, N.J. Prentice Hall; New York: Abrams, 2000.

- Gerdts. William H. Art Across America: Two Centuries of Regional Painting, 1710-1920. New York: Abbeville Press, 1990.

- Novak, Barbara. American Painting of the Nineteenth Century. New York: Harper and Row, 1979.

- Prown, Jules David. American Painting from its Beginnings to the Armory Show. New York: Rizzoli, 1987.

Have you uncovered the mysteries of your object? Sometimes it is very difficult—or impossible—to determine an artwork’s maker or history. If that is your conclusion, do not feel discouraged. If you enjoy your treasure and want to preserve it for years to come, there is plenty to learn about its value and how to properly care for it.

How Much Is Your Object Worth? – Researching Your Art

It is hard to establish fixed values for antiques, artworks, and other collectible items. The amount asked or offered is determined by many factors, including the condition of the object, personal interests of both the seller and the purchaser, and trends in the market. According to Smithsonian Institution policy, no staff member may offer monetary evaluations. However, the following guidelines should help you find an approximate value for your artwork.

First, consult price guides to determine current sale and auction prices. Some price guides are available on the Internet, but most come in books or offline formats. Specialized university or art museum libraries and larger public libraries often carry these guides. Price indexes are usually published annually and cover international auctions and galleries.

PRICE GUIDES

ADEC: International Art Prices

Art Sales Index

Davenport’s Art Reference & Price Guide

International Auction Records

Leonard’s Annual Price Index of Art Auctions

For prints, check the following resources:

Gordon’s Print Price Annual

Contemporary Print Portfolio

Lawrence’s Dealer Print Prices International

ONLINE PRICING RESOURCES

invaluable.com

artprice.com

artnet.com

AskArt.com

FindArtinfo.com

MutualArt.com

APPRAISALS & APPRAISERS

Consider finding an appraiser to determine the value of your artwork. Appraisers are trained specialists who work for a fee. They evaluate your piece and give you a written statement of its value. Although the following organizations do not provide appraisals themselves, they each publish a directory of their members. Always seek an appraiser with an expertise in the type of artwork you own.

American Society of Appraisers

11107 Sunset Hills Road, Suite 310

Reston, VA 20190

(703) 478-2228 or 1-800-ASA-VALU

www.appraisers.org

Appraisers Association of America

212 West 35th Street, 11th Floor South

New York, NY 10001

(212) 889-5404

www.appraisersassoc.org

International Society of Appraisers

303 West Madison Street, Suite 2650

Chicago, IL 60606

(312) 981-6778

www.isa-appraisers.org

AUCTION HOUSES

Some auction houses host free “open house” days where visitors can bring in their artworks and have auction-house staff members share their expertise. Other houses allow owners to mail their information with a photograph, and their experts will respond. To find an auction house in your area, search online for “fine art auction houses.”

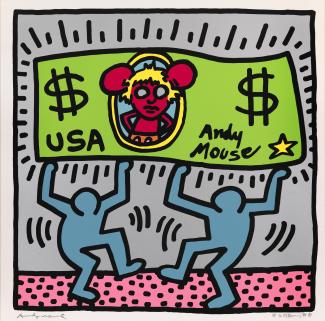

Want to Research Prints or Find Posters? – Researching Your Art

Do you have a print that you want to learn more about? Since artists often use printmaking media to create “multiples,” how can you tell whether what you own is an original print or a reproduction copy?

It can be difficult to answer these questions without taking the item to a museum print curator, auction house or certified art appraiser. The condition of a print will also be an important factor in determining its market value. To begin your research, look for a catalogue raisonné (a complete listing of the artist’s works), if one has been published for that artist.

Traditionally, printing has been defined as the transferring of ink from a prepared printing surface (a wood block, metal plate or stone carrying the image) to a piece of paper or other similar material. Techniques include three basic types—the ink is on the raised parts of the printing surface (relief), in lowered grooves (intaglio) or on the surface itself (planographic). Common relief techniques include woodcuts and linocuts. Intaglio processes include etchings and engravings. Planographic processes include lithography and serigraphy. Each technique maintains the character of the marks made by the artist during the creative process. Other techniques include monotypes and digital prints or combinations of more than one technique.

Prints exist in multiples. Each impression is considered to be an original. The total number of prints (or impressions) made of one image is an “edition.” The number may appear on the print with the individual print number as a fraction, such as 5/25, meaning this particular print is the fifth of twenty-five produced.

Reproductions are often incorrectly referred to as prints. Items advertised as fine-art prints or limited edition prints are sometimes photomechanical reproductions of paintings or drawings. Such reproductions use the same commercial printing processes used in producing magazine illustrations. The artist’s involvement is not required. Reproductions have the virtue of being less expensive than originals, but they are not considered original artworks.

PRINT INFORMATION RESOURCES

Cahn, Joshua Binion, ed. What is an Original Print? Principles Recommended by the Print Council of America. New York: Print Council of America, 1964.

Currier & Ives: A Catalogue Raisonné: A Comprehensive Catalogue of the Lithographs of Nathaniel Currier, James Merrit Ives, and Charles Currier, including Ephemera Associated with the Firm, 1834–1907. Detroit: Gale Research Company, 1984.

Gascoigne, Bamber. How to Identify Prints. A Complete Guide to Manual and Mechanical Processes from Woodcut to Ink Jet, rev. ed. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2004.

Griffiths, Antony. Prints and Printmaking: An Introduction to the History and Techniques. London: British Museum, 1980.

Nadeau, Luis. Encyclopedia of Printing, Photographic and Photomechanical Processes. Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada: 1994.

Riggs, Timothy. The Print Council Index to Oeuvre-Catalogues of Prints by European and American Artists.Millwood, N.Y.: Kraus International Publications, 1983. (For an updated online version see printcouncil.org.)

Ross, John, and Clare Romano. The Complete Screenprint and Lithograph: The Art and Technique of the Screen Print, the Lithograph, Photographic Techniques, Care of Prints, the Dealer and the Edition, Collecting Prints, Print Workshop, Sources and Charts. New York: Free Press, 1974.

Stauffer, David McNeely, and Mantle Fielding. American Engravers upon Copper and Steel. New Castle, Del.: Oak Knoll Books, 1994.

Steiner, Bill. Audubon Art Prints: A Collector’s Guide to Every Edition. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 2003.

Turner, Silvie. Print Collecting. New York: Lyons & Burford, 1996.

Watrous, James. American Printmaking: A Century of American Printmaking, 1880–1980. Madison: University of Wisconsin, 1984.

SELECTED INTERNET RESOURCES

To learn more about prints, techniques of printmaking, and determining “authenticity” or to help establish the value of your prints, see the following Web sites.

- International Fine Print Dealers Association (IFPDA) – ifpda.org

- International Print Center New York – ipcny.org

- MoMA: What is a Print? – https://www.moma.org/interactives/projects/2001/whatisaprint/print.html

- The Print Council of America – printcouncil.org

POSTER AND REPRODUCTION SOURCES

Is your love of fine art deeper than your pocketbook? Would you be happy with a reproduction, poster, or slide of a famous work? Most local print and frame shops have catalogs of commercially available posters. Or try searching the Web. Just use your favorite search engine and type in “art posters” or “art reproductions.” Remember that some artworks are not reproduced in poster or slide format.

allposters.com

art.com

Barewalls.com

postershop.com

Davis Art Images

50 Portland Street

Worcester MA 01608

(800) 533-2847

davisartimages.com

Museum Gift Shops

If you’re longing for a specific image, and you know which museum owns the artwork, contact that museum’s gift shop to see if a poster or reproduction is available.

- Art Institute of Chicago (800) 518-4214 artinstituteshop.org

- Boston Museum of Fine Arts (617) 369-3575 mfa.org/visit/shops

- Metropolitan Museum of Art (800) 662-3397 store.metmuseum.org

- Museum of Modern Art (800) 793-3167 momastore.org

If you’re still unable to locate a particular image, some companies may help you locate a hard-to-find poster or reproduction for a fee.

Print Finders

50 North 8th Street

Ste. Genevieve, MO 63670

(888) 997-6783

printfinders.com

Haddad’s Fine Arts

(800) 942-3323

haddadsfinearts.com

**not available for sale to individuals; ask your local gallery to order for you

New York Graphic Society

130 Scott Road

Waterbury CT 06705

(800) 677-6947

**not available for sale to individuals; ask your local gallery to order for you

How to Care for Your Collections – Researching Your Art

Regardless of the monetary value of your artwork, if it is personally meaningful, you should consider having the object conserved. It is very important to have trained professionals do the job. Your local art museum, gallery, or historical society can recommend reputable conservators in your area. For guidelines on selecting a conservator and a list of professional conservators in your area, contact the following organizations:

American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works (AIC)

1156 15th Street, NW, Suite 320

Washington, DC 20005-1714

Phone: (202) 452-9545

www.culturalheritage.org

Staff at the Smithsonian’s Museum Conservation Institute are often asked questions about caring for and preserving artifacts and heirlooms. While they cannot give advice on specific items, they have broad guidelines and strategies for artifact and collection care. For access to these resources, many of which are online, go to the Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute’s website.

Library of Congress

Preservation Directorate

101 Independence Avenue, SE

Washington DC 20540-4500

The Library of Congress also provides useful advice on preserving works on paper (drawings, prints, posters) and on caring for books, photographs, videos, and so forth. The Library of Congress has online publications that answer questions related to the care, handling, and storage of valuable collections, which can be found at www.lcweb.loc.gov/preservation/.

CONSERVATION ORGANIZATIONS

The following organizations are primarily geared toward professionals, but they do serve the general public, often providing lectures and workshops in collections care.

The Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts (CCAHA)

264 South 23rd Street

Philadelphia PA 19103

(215) 545-0613

www.ccaha.org

Northeast Documentation Center (NEDCC)

100 Brickstone Square

Andover MA 01810-1494

(978) 470-1010

www.nedcc.org

Regional Alliance for Preservation (RAP)

A consortium of regional conservation centers.

http://rap-arcc.org/

ADDITIONAL CONSERVATION READING

Bachmann, Konstanze, ed. Conservation Concerns: A Guide for Collectors and Curators.Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992.

Clapp, Anne F. Curatorial Care of Works on Paper. Oberlin, Ohio: Intermuseum Conservation Association, 1978.

Dollof, Francis W., and Roy L. Perkinson. How to Care for Works of Art on Paper. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1979.

Ellis, Margaret Holben. The Care of Prints and Drawings. Nashville: American Association for State and Local History, 1987.

Keck, Caroline. A handbook on the care of paintings. Nashville: The American Association for State and Local Histories, 1965.

Long, James S. Caring for Your Family Treasures. New York: Heritage Preservation and H.N. Abrams, 2000.

National Committee to Save America’s Cultural Collections. Caring for Your Collections.New York: H.N. Abrams, 1992.

Simpson, Mette Tang, and Michael Huntley, eds. Sotheby’s Caring for Antiques: a guide to handling, cleaning, display and restoration. London: Conran Octopus, 1992.

Zigrosser, Carl, and Christa M. Gaehde. A Guide to the Collecting and Care of Original Prints. New York: Crown Publishers, 1969.

COLLECTION DOCUMENTATION

Caring for your collection extends beyond maintaining the physical condition of the objects. It is important to keep good object records and a collection history. This data will be invaluable for insurance purposes in case of theft or disaster. Be sure to create a folder for each object in your collection.

In your file, include the following items:

- color photographs of the object, including full-view and details—front, back, framed, unframed. Document multiple views of three-dimensional works.

- purchase date and price

- vendor data

- artist/maker information including life dates

- title of work

- detailed description of object’s subject matter or type of work

- date of work

- dimensions—framed and unframed for two-dimensional works. Overall, object, and base measurements for three-dimensional works.

- media and support data

- detailed description of object—include location of scratches, losses, dents, abrasions, and so on

- copies of all conservation and appraisal reports

- text of inscriptions, markings, and labels

- ownership history (“provenance”)

- bibliographic information if your work is cited in any exhibition catalogues, auction catalogues, or catalogues raisonné

- exhibition and loan history

See the Getty website for information on protecting cultural objects through international documentation standards at www.getty.edu/conservation/

In the unfortunate event your artwork gets stolen, here are important resources:

International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR)

500 Fifth Avenue, Suite 935

New York NY 10110

(212) 391-6234

www.ifar.org

Select the Collector’s Corner link. National Stolen Art File

https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/violent-crime/art-theft

Want to Learn More? – Researching Your Art

For further information on materials, terms, or techniques, please check the books listed below.

- Carr, Dawson W., and Mark Leonard. Looking at Paintings: a Guide to Technical Terms. Malibu, Calif.: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1992.

- Mayer, Ralph. The Artist’s Handbook of Materials & Techniques. New York: Viking, 1991.

- Taylor, Joshua C. Learning to Look: A Handbook for the Visual Arts. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

BIBLIOGRAPHIES

If you want to research a bit more, check out the following bibliographies.

Artists by Region

Learn more about artists who were active in your state or region of the U.S.

Artists by Occupation

Resources on architects, craft and design artists, folk arts, foundries, graphic artists, illustrators, photographers, sculptors, and artists who specialized in miniatures or silhouettes.

Minority Artists Biographical Sources

Sources on African American, Asian American, Latino, Native American, women, and hearing impaired artists.

Artist Dictionaries and Other Sources

Artist biographical dictionaries, obituary sources, dictionaries for signatures and monograms, and a directory of artists’ materials and suppliers.